On October 8, 2025, deadly clashes between the Pakistani army and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) fighters in the border province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa left dozens dead. Islamabad accuses Kabul of harboring and supporting the insurgents, with India’s discreet backing. Kabul retorts that Pakistan violated its airspace by bombing border areas and even the capital. The Taliban government claims to have retaliated, killing 58 Pakistani soldiers, a figure disputed by Islamabad. This renewed tension is part of a longer-standing dispute over the Durand Line, drawn in 1893, which Afghanistan has never recognized as a legitimate border.But the issue goes beyond a simple border dispute. In the background, a strategic realignment is taking shape in which India appears to want to play a pivotal role. By welcoming the Taliban foreign minister in October, Delhi signaled an unprecedented rapprochement with the Afghan regime, as it seeks to weaken Pakistan’s influence following tensions between India and Pakistan in the spring. This new Kabul-Delhi axis could open up opportunities for other powers, notably Israeli leaders, who see India’s growing strength as a lever for extending their influence towards Central Asia, in the face of Iran and the Sino-Russian axis.

In this context, the United States is reappearing on the Afghan chessboard. Donald Trump recently described the withdrawal from the Bagram base in 2021 as a “strategic mistake” and announced the US intention to return there. The current climate of tension, creating a need for “stabilization,” could legitimize this return. Bagram, the former epicenter of the U.S. military presence, is regaining major geopolitical value in the Sino-American competition.

On October 11-12, 2025, heavy clashes and firing echoed along the 2,600-km border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Afghan Taliban forces launched fierce attacks on Pakistani army posts, seizing outposts in provinces like Kunar and Helmand. Pakistan hit back with artillery and tanks, closing border crossings. The clash left over 80 dead in total, the worst since the Taliban seized power in Kabul in 2021. But this isn’t a sudden fight. It’s a flare-up of a 130-year-old grudge, fuelled by a shaky border, militant hideouts, and broken trust. The Afghanistan-Pakistan rift centres on their disputed, tribal border–Durand Line. Pakistan wants it fenced, claiming security, while Afghanistan rejects it as a colonial-era line.

Tensions escalated on October 9-10 when Pakistan bombed parts of Kabul and eastern Afghanistan, claiming to hit Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) hideouts. Afghanistan called it an airspace violation and attacked Pakistani border posts in response. Pakistan accuses the Taliban of sheltering TTP fighters, but Kabul denies it. Since the Taliban’s 2021 takeover, TTP attacks in Pakistan have surged over 600 this year. What is border dispute on Durand Line and Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud ?

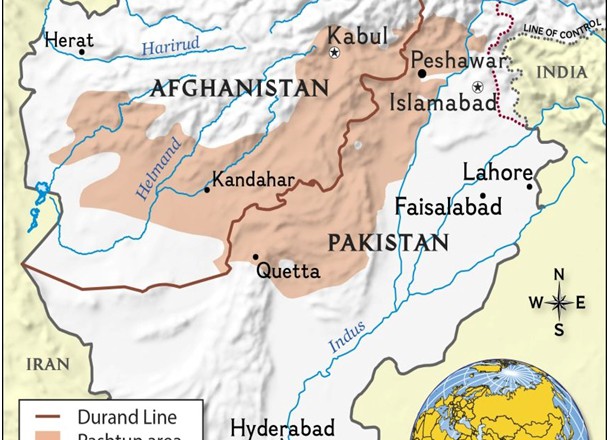

The Durand Line, a 2,640 km border from Iran to India’s PoK — is officially Pakistan’s frontier but rejected by Afghanistan as a colonial division that splits Pashtun families. Since 2017, Pakistan has fenced much of it, angering locals. At the centre of current tensions is Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, leader of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) since 2018. A South Waziristan-born cleric and militant, he’s unified TTP factions, expanded the group to about 30,000 fighters, and intensified attacks on Pakistani forces. Pakistan accuses him of orchestrating thousands of deaths and says it killed him in a Kabul air-strikes — but an audio clip viral on open source intel suggests he may still be alive. The Durand Line was actually a colonial creation, not a mutual border. In 1893, British diplomat Henry Mortimer Durand and Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman Khan drew it to serve British interests—mainly as a buffer against Russia. In exchange for arms and subsidies, Afghanistan ceded tribal regions like Waziristan. The border was imposed without surveys or local consent, splitting Pashtun tribes overnight.

Despite minor adjustments in 1919, the line’s essence remained. After 1947 partition of India, Pakistan claimed the British side as its border, but Afghanistan rejected it as illegitimate. Since then, the Durand Line has remained a source of tension—contested, fenced, and unresolved. Durand line split Pashtun lands between Afghanistan and Pakistan. This region is home to about 50 million people. Partition of this land sparked Afghanistan’s ‘Pashtunistan’ ambitions for a greater homeland. In the 1950s–60s, Afghanistan supported anti-Pakistan rebels and opposed Pakistan at the UN. The 1979 Soviet invasion turned the border into a jihad route, with Mujahideen trained in Pakistan. In the 1990s, Pakistan backed the Taliban to secure influence in Kabul, but after 9/11, the same border became a militant corridor for Al-Qaeda and the TTP.

In this context, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan has left a strategic vacuum that the United States is struggling to fill. Washington is seeking regional support. Pakistan, with its location, experience in Afghanistan, and formidable intelligence services, is reemerging as a key player. The US’s belated attempt to recover the Bagram base is a sign of this. In the absence of a credible alternative, Islamabad is once again becoming the default partner. Growing tensions between the United States and India. While Washington has long invested in this Indo-Pacific partnership, economic disagreements, visa issues, and New Delhi’s rapprochement with Moscow and then Beijing are complicating the relationship. The “Make in India” program, seen as competitive, adds to these tensions. In this context, Pakistan is regaining its value as a balancing force.

Finally, the rapprochement between Islamabad and Washington is also based on privileged access to rare earth minerals in Balochistan. But this resource diplomacy remains fragile. The region, historically marginalized, has benefited from neither infrastructure nor development despite decades of exploitation. The mining law adopted in 2025, which strengthens federal control, was perceived as a challenge to provincial autonomy. Opposition is widespread, extending even to religious parties that are generally absent from such debates. This opposition reveals a major risk: exploiting resources without involving local communities fuels frustration. What is presented as a national salvation can be experienced as dispossession. Thus, Pakistan’s supposed “renaissance” appears less like a structured renewal than a response to pressure. Until internal imbalances (fragile governance, regional inequalities, political mistrust) are addressed, external successes will remain precarious.

An American return to Afghanistan, under the guise of fighting terrorism or regional stabilization, would profoundly redraw the balance of power. Washington could use the Afghan-Pakistani conflict as leverage to reposition its forces near Iran, China, and Central Asia. In this tense context, Beijing—which has significant investments in both Pakistan and Afghanistan—is calling for dialogue to avoid an uncontrollable escalation. Similarly, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey could play a mediating role. But as long as the border issue remains unresolved and the India-Pakistan rivalry intensifies, a lasting ceasefire seems illusory. On the other hand, a new chapter in the global competition for Asia may well be unfolding.